The Teatro dell'Opera di Roma is a major opera house in Rome. Originally opened in November 1880 as the 2,212-seat Costanzi Theatre, it has undergone several changes of name as well modifications and improvements. The present house seats 1,600. Over one hundred years of success have brought the most acclaimed voices, the most prestigious sticks, and the notes of musicians who have marked its destiny to the Teatro dell'Opera di Roma: Pietro Mascagni, Giacomo Puccini, Ottorino Respighi, have delivered it to the honors of history of Italian melodrama as the cradle of 20th-century opera and musical theater.

Original Teatro Costanzi: 1880 to 1926

The Teatro dell'Opera was originally known as the Teatro Costanzi after the contractor who built it, Domenico Costanzi (1819–1898). It was financed by Costanzi, who commissioned the Milanese architect Achille Sfondrini (1836–1900), a specialist in the building and renovation of theatres. The opera house was built in eighteen months, on the site where the house of Heliogabalus stood in ancient times, and was inaugurated on 27 November 1880 with a performance of Semiramide by Gioachino Rossini.

Designing the theatre, Sfondrini paid particular attention to the acoustics, conceiving the interior structure as a "resonance chamber", as is evident from the horseshoe shape in particular. With a seating capacity of 2,212, the house had three tiers of boxes, an amphitheater, and two separate galleries, surmounted by a dome adorned with splendid frescoes by Annibale Brugnoli.

Costanzi was obliged to manage the theater himself. Under his direction, and despite financial problems, the opera house held many world premieres of operas, including Cavalleria Rusticana by Pietro Mascagni on 17 May 1890. For a brief period, the theatre was managed by Costanzi's son, Enrico, who gained renown by organizing another great premiere, that of Tosca by Giacomo Puccini on 14 January 1900.

In 1907, the Teatro Costanzi was purchased by the impresario Walter Mocchi (1871–1955) on behalf of the Società Teatrale Internazionale e Nazionale (STIN). In 1912 Mocchi's wife, Emma Carelli, became the managing director of the new Impresa Costanzi, as the theatre was later known, following various changes in the company structure. During the fourteen years of her tenure, major works which had not been performed before in Rome (or even in Italy) were staged. These included La fanciulla del West, Turandot and Il trittico by Giacomo Puccini; Parsifal by Richard Wagner; Francesca da Rimini (Zandonai) by Riccardo Zandonai; Boris Godunov by Modest Mussorgsky; Samson et Dalila by Camille Saint-Saëns and many others. Diaghilev's Ballets Russes also performed.

Restructured Teatro Reale dell'Opera: 1926 to 1946

In November 1926 the Costanzi was bought by the Rome City Council and its name changed to Teatro Reale dell'Opera. A partial rebuilding ensued, led by architect Marcello Piacentini and lasting fifteen months. The house re-opened on 27 February 1928 with the opera Nerone by Arrigo Boito.

Chief among several major changes was the relocated entrance, from the street formerly known as Via del Teatro (where the garden of the Hotel Quirinale is now) to the opposite side, where Piazza Beniamino Gigli exists today. In addition, the amphitheater inside the theatre was replaced by the fourth tier of boxes (now the third tier) and a balcony. The interior was embellished by new stuccowork, decorations, and furnishings, including a magnificent chandelier measuring six meters in diameter and composed of 27,000 crystal drops.

Above the proscenium arch is a plaque commemorating the rebuilding: "Vittorio Emanuele III Rege, Benito Mussolini Duce, Lodovicus Spada Potenziani, Romae Gubernator Restituit MCMXXVIII—VI”". Confusingly the dates appear to be back to front. (The VI refers to the sixth year after the Fascist's March on Rome of 1922.)

Present Teatro dell'Opera di Roma: from 1946

Following the end of the monarchy, the name was simplified to Teatro dell'Opera and, in 1958, the building was again remodeled and modernized. Rome City Council again commissioned architect Marcello Piacentini, who radically altered the building's style, notably with regard to the facade, entrance, and foyer, each of these taking the form we know today.

The theater's legendary acoustics still bear comparison with any other auditorium in the world. The seating capacity is about 1,600. The house was retrofitted with air-conditioning subsequent to a restoration, which provided improvements to the interior. The stucco work was completely restored, the great proscenium arch strengthened, and a parquet floor of solid oak blocks laid to replace the previous one.

On 2 January 1958, the theater was the venue for a controversial performance of Norma starring Maria Callas in the presence of the President of Italy: for health reasons, Callas abandoned the performance after the first act (the opera company had not engaged an understudy).

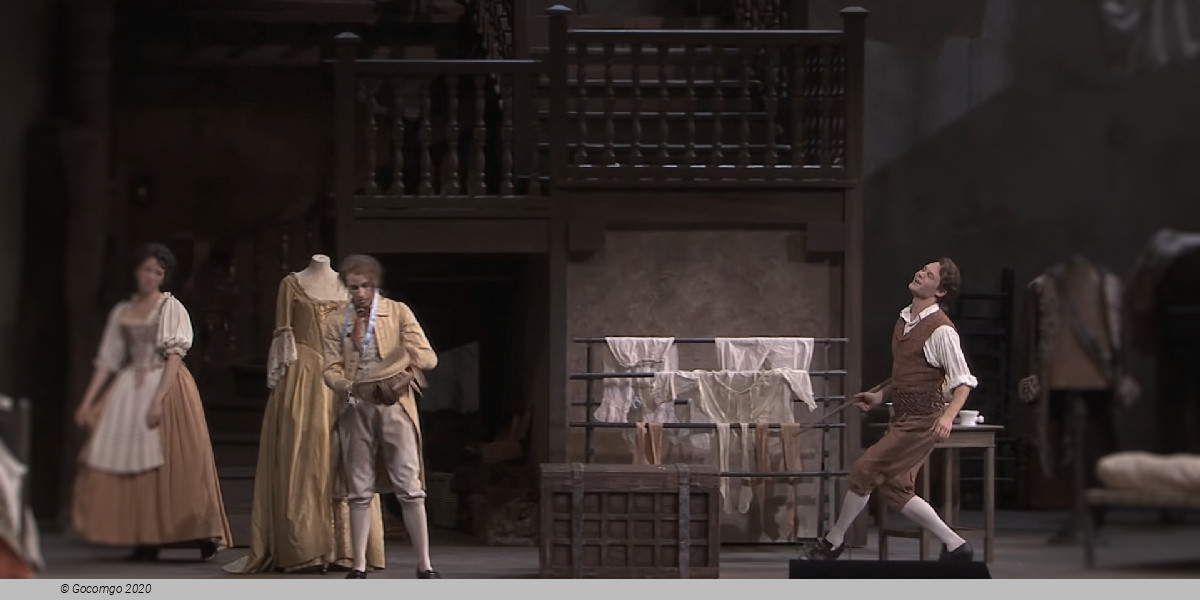

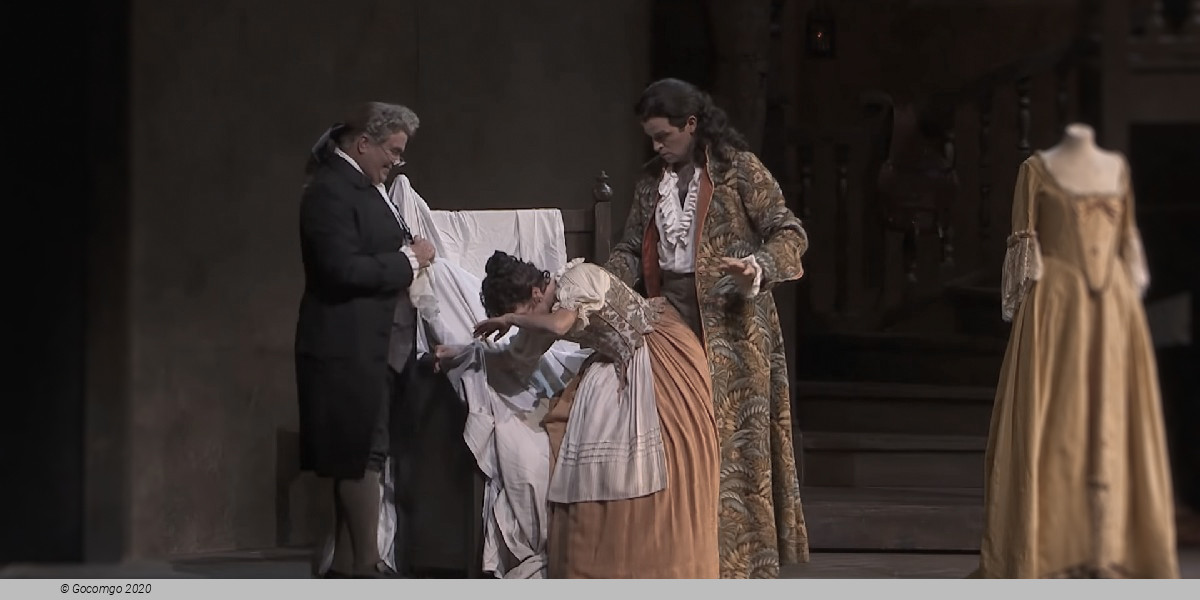

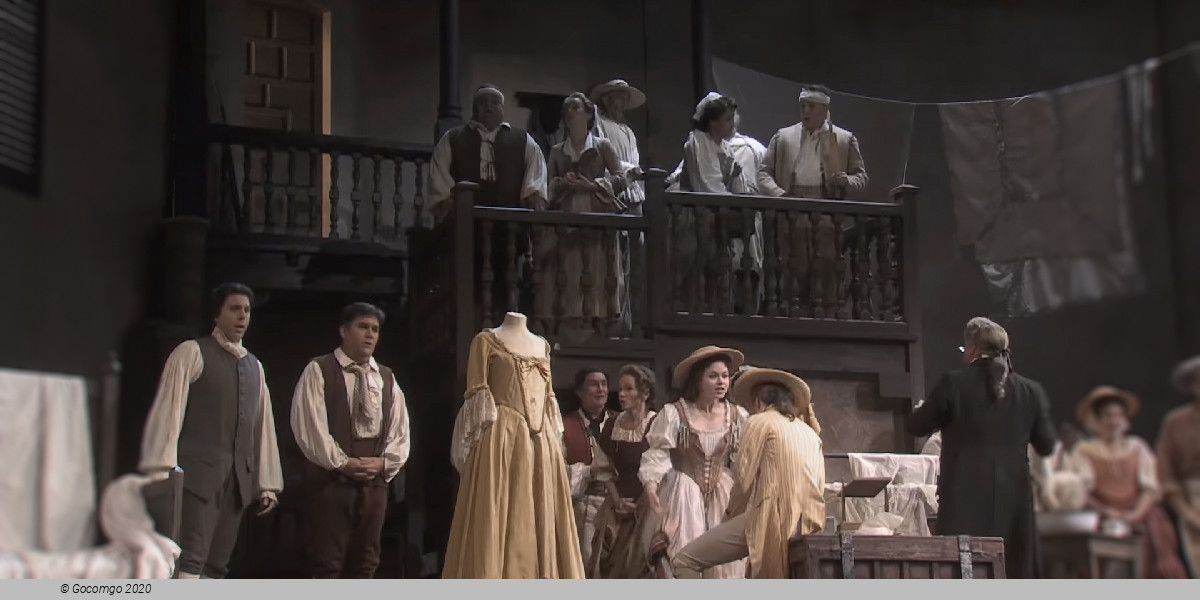

The post-war period saw celebrated productions, including Mozart's Le nozze di Figaro in 1964 and Verdi's Don Carlo in 1965, both conducted by Carlo Maria Giulini and directed by Luchino Visconti.

In the 1950s and 1960s, the Director was Riccardo Vitale (father of actress Milly Vitale).

In 1992, Gian Carlo Menotti was appointed Artistic Director of the Teatro dell'Opera di Roma, a post he maintained for two years before being asked to resign over conflicts with the theatre's managers involving Menotti's insistence on staging Wagner's Lohengrin.

From 2001 to 2010, the music director and chief conductor of the company were Gianluigi Gelmetti. He was due to be succeeded in these posts by Riccardo Muti, as announced in August 2009, but Muti demurred, citing in La Repubblica in October 2010 "general difficulties that are plaguing the Italian opera houses". Later, Muti assumed a role similar to that of a music director but without a title. Notable productions under Muti have included Gluck's Iphigénie en Aulide (2009), Verdi's Nabucco (2011), Simon Boccanegra (2012), and Ernani (2013).

Daniele Gatti was first guest-conducted with the company during the 2016–2017 season. He returned for subsequent guest engagements in each of the following two seasons. In December 2018, the company announced the appointment of Gatti as its new music director, with immediate effect. Gatti is scheduled to stand down as the company's music director on 31 December 2021. In June 2021, the company announced the appointment of Michele Mariotti as its next music director, effective 1 November 2022, with an initial contract of 4 years.

Piazza Beniamino Gigli

Piazza Beniamino Gigli